Gateway to the Gulf - Perdido Pass - A brief history

Perdido Pass - Orange Beach's best known landmark

Photo by Shelley Patterson, C-Shelz Photography flying with Lost Bay Helicopters.

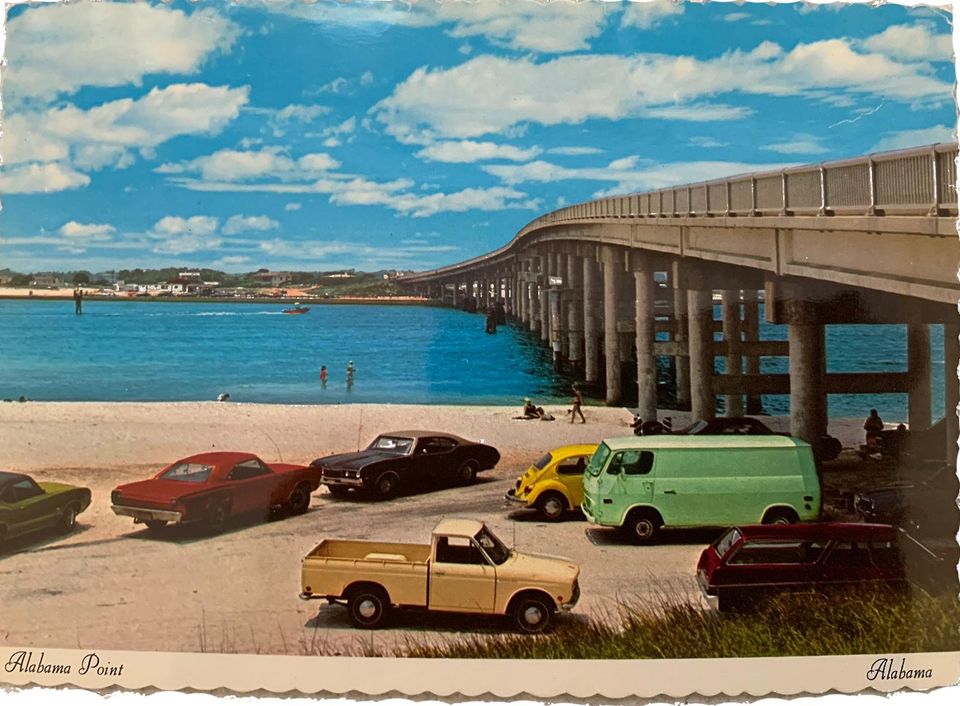

Photos above are from Thigpen Photography/Insight Concepts and Margaret Childress Long & Michael D. Shipler's book, "The Best Place To Be: The Story of Orange Beach, Alabama".

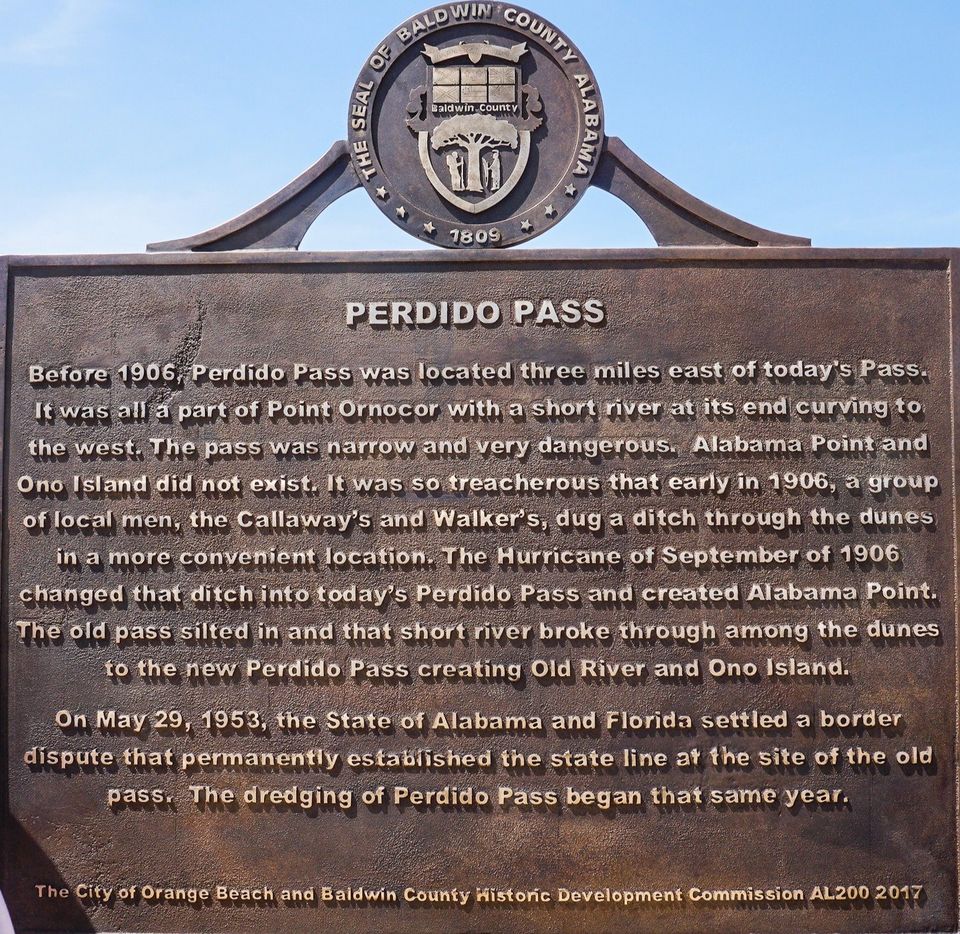

After several incidents including a waterspout waylaying a boat, the Ellen C, while in the pass and injuring town forefather Amel Callaway’s wife, Mildred, locals began searching for an alternative.

In 1906, Herman Callaway led the effort to dig a shallow ditch across the dunes at the current location of Perdido Pass. There was a basic cut established and then on Sept. 27, 1906 a major hurricane blew open the pass with its tidal surge. But it was anything but safe.

“Rufus (Walker) Sr. got killed on on the Sea Duster while trying to navigate the pass,” former charter fisherman Earl Callaway said in a 2017 interview with the OBA Community Website. “And that’s one reason why we have rocks out there today. That pass was so dangerous. A wave got him, he fell and broke his neck and it killed him. Then they started putting the pressure on the Legislators. They were tearing up boats hand over fist out there.”

Earl Callaway said it took a bit of gumption and a bit of finesse to negotiate the pass in those days.

“We’d sit out there and wait, kinda like a surfer,” Callaway said. “When it came to hit it, buddy you hit it. And when that wave hit that stern, my old man taught me as soon as it comes down you get a bite on it. Whatever way that wheel was turning you better turn it the other way. You tried to shoot through the hole. And if it was too darn rough you had to go all the way to Pensacola to go in Pensacola Pass and come back that way.”

The first attempt at dredging the pass was a crude one, according to Long’s and Shipler’s book.

“To keep the new pass channel clear in the early days, Ed Frederick was paid by the federal government to ‘blow out’ the channel,” the book states. Frederick owned a powerful tugboat which he would anchor in the channel on an outflowing tide and kick the sand out with the force of his propellers. Not the most effective way to clear a channel but it worked.”

The channel was still a moving target with sand shifting it or filling it in.

“Like the old pass there were no navigational aids other than the sharp eyes and seasoned minds of capable seamen,” the book states. “According to Roland Walker Sr., when the tide was low you could easily run aground in the shifting channel.”

Roland Walker Sr. said during his lifetime the channel moved a quarter to a half mile and some days if the Gulf was really rough returning fishing boats would have to go to Pensacola Pass to get home.

In the early 1950s Roland Walker Sr. and Willard Morrill and other members of the Orange Beach Fishing Association began petitioning the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources for regular dredging and navigational markings for the pass.

The state first dredged the pass in 1953 and subsequently in 1955, 1959 and again in 1962. In the interim, the Army Corps of Engineers rejected a plan to make improvements to the navigation of the pass because it was deemed the maintenance of it would be too costly.

“Most of the later dredging was done for the protection of the base of the newly constructed Perdido Pass Bridge,” the book states.

Roland Walker Sr. and others in the Orange Beach Fishing Association presented a report on the economic impact of the fishing industry to Congress that detailed how much money boats were making annually, the loss of trips when the pass was unnavigable and the extra cost when boats were forced to use Pensacola Pass.

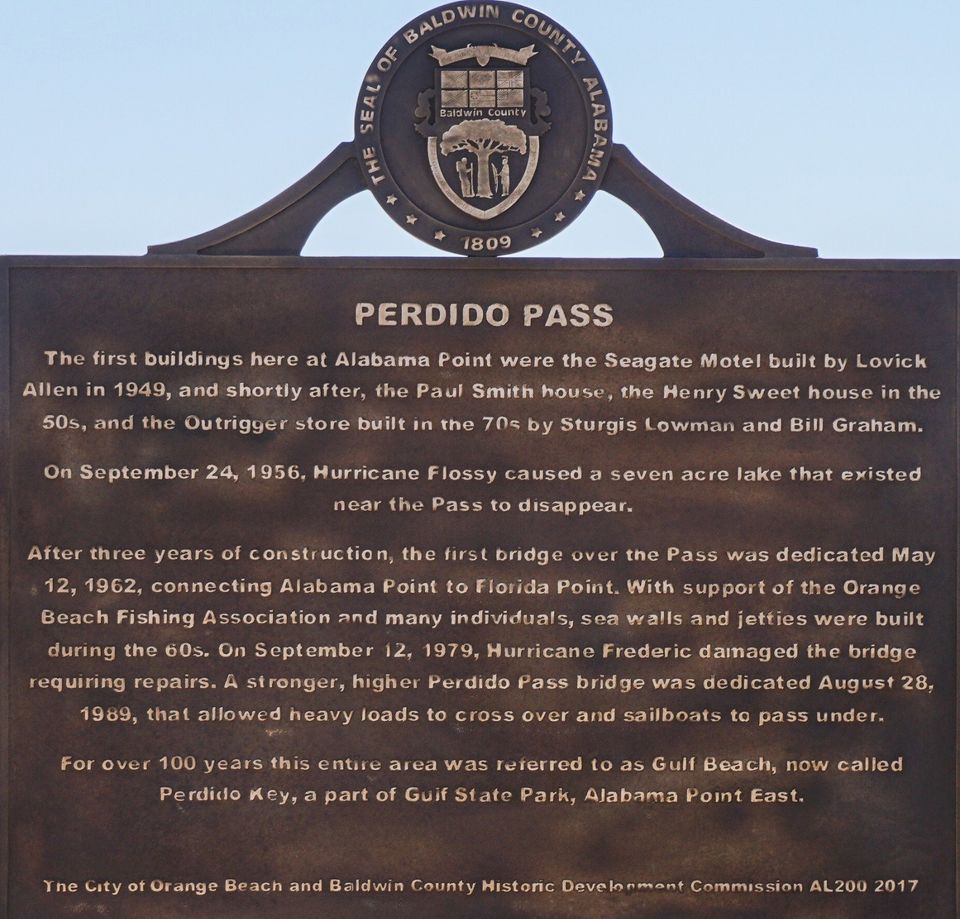

Two hurricanes – Flossy on Sept. 24 of 1956 and Betsy on Sept. 8 1965 – played an important role in finally getting some serious improvements according to Long’s and Shipler’s book. A man named Henry Sweet – who just happened to be the head of the Mobile Division of Army Corps of Engineers – built a house on the west side of Perdido Pass in the area where The Gulf restaurant is today. At one point there was a lake in front of his house. Flossy removed the lake and a lot of land from in front of his house. The answer to this was a seawall and building jetties. Those failed to keep Betsy from sweeping away even more leaving the Sweet home hanging over the pass.

As a result, Sweet sued the state for the loss of his house and won. After Betsy a new seawall was built, more jetties were put in, navigational aids added and the channel was dredged to clear all the sandbars.

Lake at Perdido Pass, circa 1965.

In the intervening years, the pass has been dredged numerous times by the Army Corps of Engineers with Alabama Congress members helping secure the funding. Sen. Richard Shelby, R-Tuscaloosa, was instrumental in getting funding for the most recent dredging projects in both 2015 and 2019.

According to Director Phillip West of Orange Beach’s Coastal Resources department the pass was dredged 23 times from 1968 to 2012.

“Various volumes (of sand were) placed in numerous areas around the inlet,” West said. “Volumes range from 10’s of thousands of cubic yards to 100,000’s of thousands.”

The two since picked up 230,000 cubic yards in the flood shoal and entrance and in 2019 290,000 cubic yards were dredged, West said.

There is the main channel from the bridge to the Gulf and depth is supposed be maintained at nine feet for most of it and 12 feet on the southern end. There are some deep holes in the pass that are as deep as 50 feet.

There are two tangent channels that are maintained as well, one going north toward Cotton Bayou and Terry Cove and another going east into Bayou St. John in the area around Cobalt restaurant and Caribe Marina. There’s a small auxiliary channel north of the bridge that connects those two channels.

At one point, according to Long, there was an effort to have the state line moved from its present location to Perdido Pass to try and get the state of Florida to help fund a bridge over the pass.

“The line was never moved from where the Flora-Bama is because in 1953 when my daddy and others owned Ono, they told Florida officials if you help the State of Alabama build the bridge, we will move the line to the pass,” Long said. “They said no, so Alabama started on the first bridge in 1959 and it was opened in May of 1962.”

Today, on an incoming tide it is estimated that 7.21 billion gallons of water enters the pass over a 12 hour period and 8.37 billion gallons of water exits the pass over a 12 hour period. That's the equivalent of 10,919 olympic-size swimming pools on an incoming tide and 12,673 olympic-size swimming pools on an outgoing tide.

Because of this large volume of water moving through Perdido Pass it can be a dangerous area to swim in when the tides are moving.

Photos above are from the dredging project in 2015.

Snorkeling Perdido Pass on a Kayak